In our quest to uncover the fate of Furness Abbey’s lost stained glass, and perhaps even find surviving pieces crafted by the master glazier John Petty, we must confront a turbulent chapter in the abbey’s history: the Dissolution of the Monasteries. This era of upheaval, instigated by King Henry VIII, not only brought an end to centuries of monastic life but also cast a long shadow over the abbey’s treasures.

The story of Furness Abbey’s destruction is inextricably linked to two men: Robert Southwell and Thomas Holcroft. Their contrasting roles in the Dissolution offer a glimpse into the complex motivations and consequences of this tumultuous period and may hold vital clues to the fate of the missing stained glass. Let’s delve into their stories and explore how their actions might have shaped the destiny of the abbey’s artistic legacy.

The Dissolution’s Grip on Furness Abbey

The Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII was a brutal period in English history, where centuries-old religious institutions were overturned and their wealth plundered by the Crown. Furness Abbey, a once-majestic Cistercian monastery nestled amidst the mist-shrouded hills of the Lancashire countryside, met a grim fate during this era. The wind howled through the crumbling arches, whispering tales of vanished monks and stolen treasures. The tale of its destruction is closely tied to two figures: Robert Southwell and Thomas Holcroft.

Southwell: The Crown’s Meticulous Surveyor

Robert Southwell, a government administrator, was dispatched north to survey and assess monastic properties for the Crown. He was known for his meticulous record-keeping and efficiency, seemingly more focused on executing orders than lining his own pockets. At Furness Abbey, he carried out his duties with an air of detached professionalism, surveying the grounds, its buildings – the soaring arches of the church, where sunlight streamed through broken windows, casting long shadows on the dusty floor, the intricate stonework of the cloisters, cold and damp to the touch, the scriptorium where monks once laboured over illuminated manuscripts, the scent of parchment and ink still lingering in the air. He noted the quality of the land, the livestock in the barns, their lowing echoing through the empty yards, the weight of the lead upon the roof, its dull sheen contrasting with the vibrant colours of the remaining stained glass, the glimmer of gold leaf within the chapel, its brilliance dimmed by years of neglect. All was meticulously recorded in his neat, precise hand.

Holcroft: The Ruthless Opportunist

However, Thomas Holcroft, a man of ambition and avarice, had other motivations. He saw the Dissolution as an opportunity for personal enrichment, grabbing land and titles left vacant by the dissolved monasteries. He gained a reputation for ruthlessness and ambition, drawing criticism for his eagerness to tear down historic buildings if it meant turning a profit. The whispers followed him north; tales of abbeys reduced to rubble, of sacred spaces desecrated, all for the clink of coins in his purse.

And here’s where the story turns darker. Holcroft was put in charge of demolishing Furness Abbey. Instead of repurposing the site or salvaging materials, he was accused of excessive destruction, essentially erasing much of the abbey from the landscape. The crash of falling masonry echoed through the valley, the air thick with dust and the scent of damp stone. Where once the abbey stood proud, now only broken walls and scattered stones remained, a testament to Holcroft’s destructive zeal.

Southwell, witnessing this wanton destruction, penned a letter to Cromwell, hinting at Holcroft’s motives: “If there is a good fee, Holcroft will take it: he has been diligent, though only put in trust to pluck down the church.” He described the shattered remnants of the great east window, its vibrant stained glass – perhaps even Petty’s masterpieces – now shards scattered amongst the weeds, glinting like jewels in the fading light.

This stark contrast between Southwell and Holcroft reveals the deeply troubling side of the Dissolution. Southwell, though participating in the King’s programme, at least seemed to have some reservations about needless destruction. Holcroft, however, represents the rapaciousness of those who profited from the Dissolution, with little regard for history or the sacredness of the site.

Why Do We Call Holcroft Ruthless?

It’s easy to label someone with such a strong word, but the evidence is there:

He was accused of being “overly zealous” in destroying Furness Abbey, not just dissolving it. This suggests going beyond simply closing the monastery down, but actively obliterating the structures.

Southwell’s comment about Holcroft seeking fees implies that profit motivated excessive demolition. This gives us a motive for the destruction – financial gain, even at the cost of the historical and cultural significance of the site.

Even in the context of the time, Holcroft was criticised for his “greed and destructive tendencies”. This tells us that his actions weren’t just typical of the Dissolution; they stood out as particularly avaricious and destructive.

This characterisation of Holcroft comes directly from the author of the “Coucher Book of Furness Abbey” itself, who provides valuable insight into the events of the Dissolution.

The Dissolution was a national tragedy, but the ruination of Furness Abbey stands as a particularly poignant example. It reminds us that history is shaped not only by grand events, but by the choices and character of individuals like Southwell and Holcroft.

Delving Deeper into the Dissolution

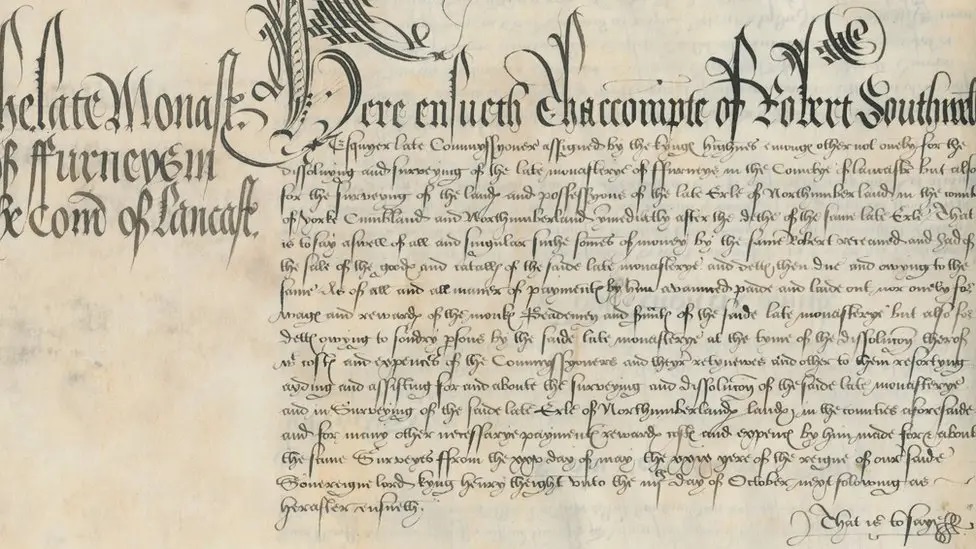

A recently uncovered document, written by Robert Southwell in 1537, sheds further light on the Dissolution of Furness Abbey. This document, found in the National Archives, reveals fascinating details about the process:

A Generous Handout: The monks at Furness Abbey were not immediately forced out but were allowed to remain at the abbey for several months. They were eventually given a generous cash handout to leave quietly, suggesting an attempt to appease local opposition to the Dissolution.

Financial Motivations: The document highlights the financial motivations behind the Dissolution, listing speculators who arrived from southern England, eager to profit from the abbey’s assets. However, many of the abbey’s assets were sold locally, including the bells, which were purchased by the “men of Kendal” for the significant sum of £80.

Missing Treasures: Intriguingly, the document notes a surprisingly small amount of precious metal altar plate seized from the monastery, leading to questions about whether the monks had already hidden some valuables before the arrival of the commissioners.

Profit and Loss: The financial accounts in the document show that the total profit from the abbey’s suppression was almost £800, but only £367 remained after expenses were paid. These expenses included the monks’ handout, the monastery’s debts, the cost of processing the lead from the abbey, and the commissioners’ own expenses.

This newly discovered document, along with the “Coucher Book of Furness Abbey”, provides a more nuanced understanding of the Dissolution and its impact on Furness Abbey. They paint a picture of a complex process driven by both political and financial motivations, with individuals like Southwell and Holcroft playing key roles in the abbey’s demise.

Insights from the “Annales Furnesienses”

The “Annales Furnesienses,” a historical record of Furness Abbey, provides a valuable glimpse into the intricate process of the monastery’s dissolution. This chronicle reveals the methodical approach taken by the commissioners, highlighting their meticulous record-keeping and adherence to procedure. It also sheds light on the fate of the abbey’s abbot, who was ultimately granted the position of rector in Dalton.

However, the “Annales Furnesienses” also exposes some inconsistencies and uncertainties surrounding the Dissolution. The chronicler notes that the commissioners were unable to determine the exact amount of money given to the monks, raising questions about the financial transparency of the process. This suggests that the monks may not have received a full and accurate accounting of the abbey’s wealth or their rightful compensation.

Furthermore, the chronicle reveals discrepancies between the accounts provided by the Receiver General and other sources, adding to the suspicion that some funds may have been mishandled or misappropriated during the Dissolution.

These inconsistencies and uncertainties presented in the “Annales Furnesienses” add a layer of intrigue to the story of Furness Abbey’s demise. They remind us that history is not always clear-cut and that even well-documented events can be shrouded in mystery and ambiguity.

Life at Furness Abbey During the Dissolution

The “Annales Furnesienses” also offers a unique perspective on life at Furness Abbey during the Dissolution. The chronicle reveals that the monks were permitted to remain at the abbey for a period after the official surrender, alongside the King’s bailiffs. Interestingly, the abbey’s usual routines, such as holding court sessions, continued during this time, albeit under the authority of Sir John Lamplugh, the Crown Agent. This suggests a period of transition and adaptation as the monks awaited their fate and the abbey’s functions were gradually transferred to the Crown.

The Aftermath of the Dissolution

The Dissolution had a profound impact on the Furness Abbey community. Not only were the monks displaced, but the local poor, who had relied on the abbey for alms and support, were left to fend for themselves. The “Annales Furnesienses” records that the abbey’s school was closed, leaving the poor boys who attended with no further education. Even those who had served the abbey, like the almsmen and widows who depended on the abbey kitchen, were dismissed with little provision for their future.

While some of the abbey’s buildings were repurposed for farming, much of the structure was left in ruins. The lead was stripped from the roofs, melted down, and likely sold for profit. This physical dismantling of the abbey symbolised the broader dismantling of monastic life and the social and economic structures it supported.

The Human Cost of Dissolution

The Dissolution of Furness Abbey was not just about the destruction of buildings and the transfer of wealth. It also had a profound impact on the lives of the monks who called the abbey home and the community that depended on it. While the monks were offered some compensation, they were ultimately displaced from their community and way of life. The local people who relied on the abbey’s charity were left without support, highlighting the social and economic disruption caused by the Dissolution.

The “Annales Furnesienses” provides a glimpse into the human cost of the Dissolution, reminding us that history is not just about grand events and powerful figures, but also about the lives of ordinary people caught in the tide of change.

#FurnessAbbey #DissolutionOfTheMonasteries #HenryVIII #TudorHistory #MonasticLife #LostTreasures #StainedGlass #JohnPetty #RobertSouthwell #ThomasHolcroft #HistoricPreservation #EnglishHeritage #LancashireHistory #CistercianMonastery #AnnalesFurnesienses #CoucherBookOfFurnessAbbey #HistoryMysteries #HiddenHistory