Standing quietly above the shifting sands of Morecambe Bay, on a prominent headland near the village of Aldingham, there’s a lonely grassy mound called Moat Hill. The Aldingham Castle history is preserved here, making this more than just another bump in the Cumbrian coastline. That mound holds the remains of something far more important: a rare and remarkable medieval castle.

The Aldingham Castle history is rich and layered, revealing the transformation of a simple ringwork into a formidable motte and bailey fortress. This site stands as a vital record of Norman military architecture and feudal power in medieval Cumbria, its story etched into the earthworks that still endure today.

🏗️ What Is a Motte and Bailey Castle?

Let’s start with the basics.

Motte and bailey castles were introduced to Britain by the Normans after 1066. They were quick to build, strategically placed, and easy to defend. The design consisted of:

A motte — a large conical mound of earth or rubble, usually topped with a timber or stone tower.

A bailey — an enclosed courtyard area at the base of the motte, where additional buildings such as stables, halls, and workshops would be located.

A ditch and timber palisade (fence) around both motte and bailey for protection.

They acted as military garrisons, noble residences, and administrative centres, often dominating their surrounding landscape. Over 600 examples are recorded across England, and many were built in newly conquered or unsettled regions.

These castles weren’t built to last forever. By the late 13th century, most had been replaced by more permanent stone-built castles — but for the 100–150 years they were in use, motte and bailey castles were the backbone of Norman control.

🔁 What Is a Ringwork, and Why Is It Rare?

Before motte and bailey castles became widespread, an earlier form of fortification was used: the ringwork. These were also earth-and-timber structures, but without the raised motte. They consisted of a defended enclosure surrounded by a ditch and earthen bank, topped with a timber palisade.

Ringworks were built and occupied from the late Anglo-Saxon period through to the later 12th century. They were used as:

Military strongholds

Aristocratic residences

Or even manorial centres

There are only around 200 ringworks recorded nationally in England, and fewer than 60 had baileys attached. That makes surviving examples rare and highly valuable for historical study — especially when they later developed into motte and bailey castles.

Exploring the Aldingham Castle history provides invaluable insight into early medieval fortifications. The evolution from ringwork to motte and bailey reflects broader shifts in military strategy and social control during the Norman occupation, making Aldingham a unique case study among English castles.

That’s exactly what happened at Aldingham. The Aldingham Castle history tells the story of this transformation.

🏰 The History of Aldingham Castle

At Moat Hill, the story begins in the early 12th century, when a ringwork was first constructed on the site. This early fortification:

Measured approximately 40 metres in diameter

Was defended by an earthen rampart around 3 metres high

Likely included wooden buildings within the enclosure

This site was built by the le Fleming family, Norman lords who had been granted the manor of Aldingham by King Henry I. The le Flemings held power in Furness for generations and played a central role in the development of the region during the medieval period.

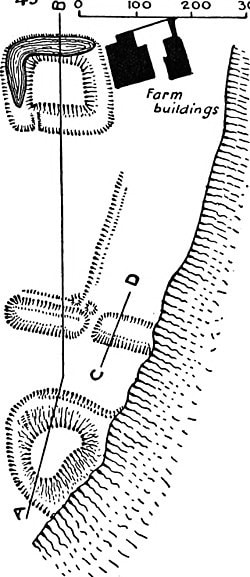

Later in the 12th century, the original ringwork was infused and heightened to form a motte, and a bailey was added to the north and north-east of the site. This marked the conversion of the site into a classic motte and bailey castle. A new ditch, around 7.5 metres wide and up to 3 metres deep, was dug around the motte.

By the early 13th century, the motte was heightened again and reinforced with a vertical timber revetment — wooden planks designed to hold up the steep earthen sides of the motte. The bailey’s own ditch, now partly infilled, still measures about 3.7 metres wide and 3.5 metres deep on its best-preserved side.

This final version of Aldingham Castle stood as a clear statement of feudal control, defence, and status. It is an important chapter in the Aldingham Castle history.

🌊 Nature’s Challenge: Coastal Erosion

The castle may have been strong against enemies — but it couldn’t resist the sea.

Moat Hill is perched on a cliff edge, and over the centuries, coastal erosion has taken a toll. Much of the seaward side of the motte and its surrounding ditch have been destroyed. Part of the bailey is gone too. What survives today is the core of the castle, still standing despite hundreds of years of wind, rain, and tide.

Even with this damage, the site is considered well-preserved — particularly for its age and coastal location. The earthworks still offer a clear picture of its layout, and the history it holds.

Archaeological investigations have helped illuminate the Aldingham Castle history, uncovering evidence of construction phases and defensive enhancements. Each discovery contributes to understanding how this site fit into the larger Norman network of fortresses and estates across the region.

🛡️ Why Moat Hill Matters Today

Moat Hill isn’t just a historic footnote. It’s a Scheduled Monument, recognised by Historic England as nationally important. It offers insight into:

The evolution of Norman military architecture

The spread and decline of ringworks and motte castles

How landowners like the le Flemings used castles to control and shape their manors

The shift from timber castles to more permanent moated sites like Moat Farm and eventually Gleaston Castle

And most uniquely, it’s one of very few confirmed examples of a ringwork that developed into a motte and bailey. That alone makes it a rare survivor — and a window into a turning point in English medieval history.

The significance of the Aldingham Castle history extends beyond the physical remains. It offers a window into medieval life, power structures, and the transition from temporary earthworks to permanent stone castles. Preserving this history ensures future generations can appreciate the enduring legacy of Norman influence in Cumbria.

🚶 Visiting Moat Hill Today

The site sits on private land, so there is no public access directly onto the motte. However, the remains are clearly visible from nearby, and respectful visitors are welcome to view from a distance.

If you’re passing through the area, consider stopping at Mote Farm — located nearby and named after the historic site. It’s a lovely place for a walk, a meal, or simply to sit and reflect on the long and layered history of this quiet coastal hill.

📚 Conclusion: A Castle in the Land

Aldingham’s Moat Hill may not have towers or turrets left to admire, but what it does have is even rarer: untouched earthwork remains of one of the few Norman castles to grow directly from a ringwork.

It stood watch over Morecambe Bay for over a century, changed form with the times, and now offers a glimpse into a period where power, land, and loyalty were measured in mounds and ditches.

In its own silent, grassy way, Moat Hill still tells its story — if you know how to read the land.