In our quest to uncover the fate of Furness Abbey stained glass, and perhaps even find surviving pieces crafted by the master glazier John Petty, we must confront a turbulent chapter in the abbey’s history: the Dissolution of the Monasteries. This era of upheaval, instigated by King Henry VIII, not only brought an end to centuries of monastic life but also cast a long shadow over the abbey’s treasures.

The Fateful Hand of Dissolution: Southwell, Holcroft, and Furness Abbey’s Lost Legacy Part 3

19 December 2024

The story of Furness Abbey stained glass destruction is inextricably linked to two men: Robert Southwell and Thomas Holcroft. Their contrasting roles in the Dissolution offer a glimpse into the complex motivations and consequences of this tumultuous period and may hold vital clues to the fate of the missing stained glass. Let’s delve into their stories and explore how their actions might have shaped the destiny of the abbey’s artistic legacy.

How the Dissolution Threatened Furness Abbey Stained Glass

The Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII was a brutal period in English history, where centuries-old religious institutions were overturned and their wealth plundered by the Crown. Furness Abbey, a once-majestic Cistercian monastery nestled amidst the mist-shrouded hills of the Lancashire countryside, met a grim fate during this era. The wind howled through the crumbling arches, whispering tales of vanished monks and stolen treasures. The tale of its destruction is closely tied to two figures: Robert Southwell and Thomas Holcroft.

Southwell: The Crown’s Meticulous Surveyor

Robert Southwell, a government administrator, was dispatched north to survey and assess monastic properties for the Crown. He was known for his meticulous record-keeping and efficiency, seemingly more focused on executing orders than lining his own pockets. At Furness Abbey, he carried out his duties with an air of detached professionalism, surveying the grounds, its buildings – the soaring arches of the church, where sunlight streamed through broken windows, casting long shadows on the dusty floor, the intricate stonework of the cloisters, cold and damp to the touch, the scriptorium where monks once laboured over illuminated manuscripts, the scent of parchment and ink still lingering in the air. He noted the quality of the land, the livestock in the barns, their lowing echoing through the empty yards, the weight of the lead upon the roof, its dull sheen contrasting with the vibrant colours of the remaining Furness Abbey stained glass, the glimmer of gold leaf within the chapel, its brilliance dimmed by years of neglect. All was meticulously recorded in his neat, precise hand.

Holcroft: The Ruthless Opportunist

However, Thomas Holcroft, a man of ambition and avarice, had other motivations. He saw the Dissolution as an opportunity for personal enrichment, grabbing land and titles left vacant by the dissolved monasteries. He gained a reputation for ruthlessness and ambition, drawing criticism for his eagerness to tear down historic buildings if it meant turning a profit. The whispers followed him north; tales of abbeys reduced to rubble, of sacred spaces desecrated, all for the clink of coins in his purse.

And here’s where the story turns darker. Holcroft was put in charge of demolishing Furness Abbey. Instead of repurposing the site or salvaging materials, he was accused of excessive destruction, essentially erasing much of the abbey from the landscape. The crash of falling masonry echoed through the valley, the air thick with dust and the scent of damp stone. Where once the abbey stood proud, now only broken walls and scattered stones remained, a testament to Holcroft’s destructive zeal.

Southwell, witnessing this wanton destruction, penned a letter to Cromwell, hinting at Holcroft’s motives: “If there is a good fee, Holcroft will take it: he has been diligent, though only put in trust to pluck down the church.” He described the shattered remnants of the great east window, its vibrant Furness Abbey stained glass – perhaps even Petty’s masterpieces – now shards scattered amongst the weeds, glinting like jewels in the fading light.

The Aftermath for Furness Abbey Stained Glass

This stark contrast between Southwell and Holcroft reveals the deeply troubling side of the Dissolution. Southwell, though participating in the King’s programme, at least seemed to have some reservations about needless destruction. Holcroft, however, represents the rapaciousness of those who profited from the Dissolution, with little regard for history or the sacredness of the site.

Why Do We Call Holcroft Ruthless?

It’s easy to label someone with such a strong word, but the evidence is there:

He was accused of being “overly zealous” in destroying Furness Abbey, not just dissolving it.

Southwell’s comment about Holcroft seeking fees implies financial motivation for excessive demolition.

Even in the context of the time, Holcroft was criticised for his “greed and destructive tendencies”.

Delving Deeper into the Dissolution

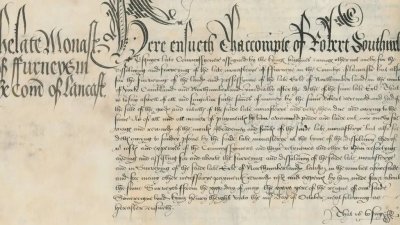

A recently uncovered document, written by Robert Southwell in 1537, sheds further light on the Dissolution of Furness Abbey:

A Generous Handout: The monks were allowed to remain for months and were paid to leave peacefully.

Financial Motivations: Southern speculators arrived hoping to profit from the abbey’s assets.

Missing Treasures: Only a small amount of altar plate was found—raising suspicion that valuables were hidden.

Profit and Loss: While nearly £800 was raised, only £367 remained after expenses.

These records help build a clearer picture of what may have happened to Furness Abbey stained glass and other artefacts now considered lost.

Insights from the “Annales Furnesienses”

The chronicle provides a glimpse into the abbey’s final days and the process of its dismantling. It notes:

The abbot became rector of Dalton.

Court sessions continued temporarily at the abbey.

Payment records were unclear, raising suspicion over funds and compensation.

The Human Cost of Dissolution

Not only were monks displaced, but the community around them suffered. Schools closed. Almsmen and widows were cut off. Children were left without education. The very social system that held Furness together was dismantled alongside the walls. And in all this loss, we must not forget the beauty — like Furness Abbey stained glass — that vanished from sight, but not from memory.